Modern Staff Engineering at a Startup

I've been attending DevOps Days in Birmingham, Alabama since its inception and have enjoyed being a part of this small tech community over the years. Last year I tried my hand at giving my first ever conference talk, which received a pretty nice reception. This year, I submitted a talk to share my experience applying my core engineering tenants at my current employer, a startup called Smartrr. What follows is the content I used for the talk, along with some of the slides I used to present.

Here's a recording of the talk, thanks to the DevOps Days Birmingham organizers!

Introduction

Today, I'm going to share with you some of what I know about DevOps, Staff Engineering, and Platform Engineering. In particular, I want to explore whether these concepts have a place in a Startup.

I argue that they do. In the end, I hope you'll agree. 🙂

My name's Chad McElligott, and I'm a Senior Staff Engineer at the New York City-based startup Smartrr, where we provide subscriptions and loyalty functionality as a service to Shopify brands. I work remotely from Huntsville, Alabama, and I've been with Smartrr for a year now. We have 18 people across our product and engineering group, which is more than half of the company as a whole.

Smartrr is a "Series A Startup." This means we've proven to investors we've found product-market fit to receive a round of funding, and we're now working to grow our customer base, broaden our reach, and stabilize our core offering. I joined Smartrr a few months after we closed our Series A. I have a general Staff engineering role, working on our cloud infrastructure but also helping to lead the product teams alongside our CTO and our Director of Product. This role is one of "leadership without authority" - I help steer the direction of the engineering group through sound reasoning, leading by example, and earning the trust of my fellow engineers. I consider these concepts of DevOps, Staff Engineering, and Platform Engineering as tools to use to lead and build that trust.

Explaining My Core Engineering Tenets

But what do these concepts of DevOps, Staff Engineering, and Platform Engineering mean?

DevOps

Maybe, being at a DevOpsDays conference, you feel you have a pretty good understanding of what DevOps means. But even among us, it's unlikely we'll universally agree on a definition. To some, it's a job title. To others, it's a way of working. Perhaps you're a software engineer who's experienced "DevOps as No Ops," resulting in you having to handle all Ops-related concerns yourself. Maybe you enjoy that, or maybe you feel it's moving us backwards.

To me, DevOps is a mentality of collaboration, automation of toil, and an embrace of modern tooling to sustain a fast flow of value to customers. It's not just leveraging the cloud, building infrastructure using code, or setting up CI/CD pipelines. And it's not just breaking down barriers to communication and collaboration. DevOps is a collection of these things, a recognition of how far we've come as an industry and the lessons we've learned, and taking advantage of that to achieve better outcomes for our customers and for ourselves.

Platform Engineering

Platform Engineering is a newer concept, made popular by the book Team Topologies by Manuel Pais and Matthew Skelton. I gave a talk about my experience as a Platform Engineer at last year's DevOps Days Birmingham, which is available on YouTube if you haven't had a chance to hear it yet.

I think of Platform Engineering as a technique for reducing the cognitive load on developers. It aims to increase product development velocity AND system stability by putting in place foundational components that support the developer's activities. Listening to podcasts like the Engineering Enablement podcast, you can hear many stories about how large organizations are building platform engineering teams to reap efficiencies and improve the developer experience.

Staff Engineering

Lastly, Staff Engineering isn't a mindset or a technique, but a role a software engineer fills within an organization, sometimes also called "Staff plus".

A progression past the "career" senior software engineer role, Staff Engineering may be best described as "servant leadership for software engineering". Senior Software Engineers are responsible for the outcomes of their work and the work of their direct team. The Staff+ role can grow that responsibility to the entire organization, but it may lose some of the individual contributorship a Senior Engineer may have grown accustomed to previously. Staff+ Engineers are often partnered with managers, directors, or VPs to bring IC-style "boots on the ground" perspective, energy, and action to their agendas. There is a lot of overlap between the "Architect" role of past generations and Staff+ engineering, and Will Larson even calls out "Architect" as one of the four "Staff archetypes" – the others being "Right Hand", "Tech Lead", and "Fixer" – in his book Staff Engineer.

Startup Culture

So what's different about working at a venture-backed startup, anyway?

Well, to grow the company, the leaders hire up, often taking on more expenditures than the company's revenue, leaning on the capital gained from investors to provide a so-called "runway" to facilitate rapid growth. As a result, the company must move fast toward growth and profitability before that runway runs out. This dynamic leads to two cultural qualities that a startup exhibits:

-

There's no time to waste. While waste is never okay, wasted time is particularly detrimental for a Startup. The development team's activities have to be hyper-focused on the organization's strategic goals while there's still enough runway to execute them. Everyone on the team needs to consider whether their activities are aligned, and, if they think they're off course, to check in and reorient. Experiments often will fail, but this isn't a waste as long as they're structured for learning and that desired lesson is learned.

-

We all wear many hats. When an organization is small, there's a lot of work to be done and seemingly nowhere near enough people to do it. As a result, someone who identifies as a front-end developer may also be performing the activities of a product designer, technical writer, product manager, quality assurance, third-party integrator, and more. As new ideas are brought to the table of how to further improve the customer experience, those who brought these ideas may end up also being responsible for prototyping or bringing the ideas to life.

These cultural qualities inform what is needed from a product development group and, in particular, a software engineering leader within that group. They can also give us hints about how DevOps, Platform Engineering, and Staff Engineering may need to be adapted to this environment.

Adapting My Engineering Tenets to Startup Culture

So, let's talk about that! How do our 3 engineering concepts change when considered through the lens of a startup culture?

DevOps at a Startup

For DevOps, it's important to keep in mind that processes are easy to change at a startup because there are so few people who need to alter their behavior. When looking to solve some problem, particularly when a tool is involved, it's best to alter your process to the tool for best results. Keeping a rigid process would require you to customize tools and possibly even build additional pieces of software, all of which are a drain on the time you could be spending creating value elsewhere.

Speaking of tools, you should try to avoid as much custom tooling as possible. This can take many forms, but may include using serverless infrastructure, leveraging SaaS tools, or choosing an open-source library. Try to go with the grain of technology where deviating doesn't provide a competitive advantage for your company, as it'll save you a lot of time and energy. Martin Fowler has a great article on his blog about this, titled Utility vs Strategic Dichotomy, if you'd like to learn more.

Lastly, when you are choosing "utility" technology, you'll want to make sure it is boring. Don't make big bets on solutions that are unfamiliar to the team or that have no community around them. If you encounter a problem, you want to be able to find a solution to it online, not be forced to code one up from scratch. Dan McKinley has a full talk dedicated to explaining this idea at boringtechnology.club.

Platform Engineering at a Startup

So how does Platform Engineering change at a Startup?

On Rebecca Murphey's new Engineering Unblocked podcast, something she said that I love is that "A company's developer experience is a product, whether anyone designed it or not." This is true even at Startup scale. You still need to monitor, deploy, track errors, read logs, and flip feature flags. The question is - Is it a pain to do these things?

When thinking about Platform Engineering at an early-stage startup, it'll certainly be a part-time hat you wear. While at one point, you may need an integrated test environment separate from production, later you may find your Platform-related concerns lower down the list of priorities. You'll find yourself putting on the Platform Engineering hat only as the need arises.

You're also not likely to have time for long-term platform-related projects. Instead, think of how to implement some value-adding component of the broader solution you have in mind. You can think big picture, and share that grander vision with your team, but you need to work in small batches, and help people understand how these smaller pieces connect to that broader vision.

Lastly, Platform Engineers at larger companies spend considerable effort ensuring smooth transitions from legacy software to modern tools and techniques. By contrast, doing Platform work at a startup mostly involves putting components in place that did not exist at all before. You'll be blazing a trail, unlocking new productivity and approaches that were previously not possible. This is a great feeling, but it can also be tricky to know - of all the possible things I could be doing, what should I do? When deciding whether to take on a platform-related project, take care to ensure you are solving the problems your organization currently has or those you see on the immediate horizon. Through boots-on-the-ground work, talking with your fellow engineers, paying attention to retrospective feedback, and periodic assessment of your Software Development Lifecycle metrics, you'll surface work that deserves attention. Sometimes though, it'll be best to leave the platform work for another day, and focus on needs elsewhere. Try to be flexible.

Staff Engineering at a Startup

Lastly, the Staff Engineer role is already well suited for work within a startup. The inherent deep technical expertise, the interest in having a broad impact, and the willingness to go where needed to solve business problems all resonate strongly in this environment.

There's a common saying in large organizations that certain senior staff "know where the bodies are buried", suggesting that they understand where technical debt lies and the context around it. It's often the role of a Staff engineer to go and find those people and write down their knowledge so decisions can be made on how to proceed. At a startup, by contrast, you can often look around after joining and easily see all the various things that need attention. You might even say there's a "trail of unburied bodies" at a startup! Startups provide the opportunity for a Staff engineer to have a tremendous impact through execution alone by reigning in this chaos and putting in place solutions that will serve the organization for years to come.

Staff engineers won't be able to stay in any one "archetype" at a startup. It is likely, due to the small size of the group, that you will be expected to be hands-on in addition to your other typical Staff+ activities. You'll be called upon for architecture work, leading projects, performing tactical tasks, and will be expected to come up with your own ideas of how to improve things and implement them without being told. Fluidity and ownership are key traits of a Staff+ engineer at a Startup.

Lastly, one perhaps less mentioned aspect of Staff+ engineering is their work doing mentorship and sponsorship to help other engineers. This can be especially important at a startup with junior talent, as they need the support, guidance, and guardrails that a staff engineer can provide.

Applying Modern Staff Engineering at a Startup

So now that we've looked at what DevOps, Platform Engineering, and Staff Engineering look like at a startup in the abstract, I'd like to share two stories with you about projects I worked on during my first year at Smartrr and how I applied these modern engineering practices we've discussed thus far.

My first story is from the beginning of my time at Smartrr. It's about the improvements we made to our QA process and how we no longer impose a merge freeze while regression testing our releases.

Second, I'll share how we've evolved our processes as we strive to continuously improve how we organize our work.

So, let's dive in!

Story 1 of 2 - Improving DevEx by Removing a Merge Freeze

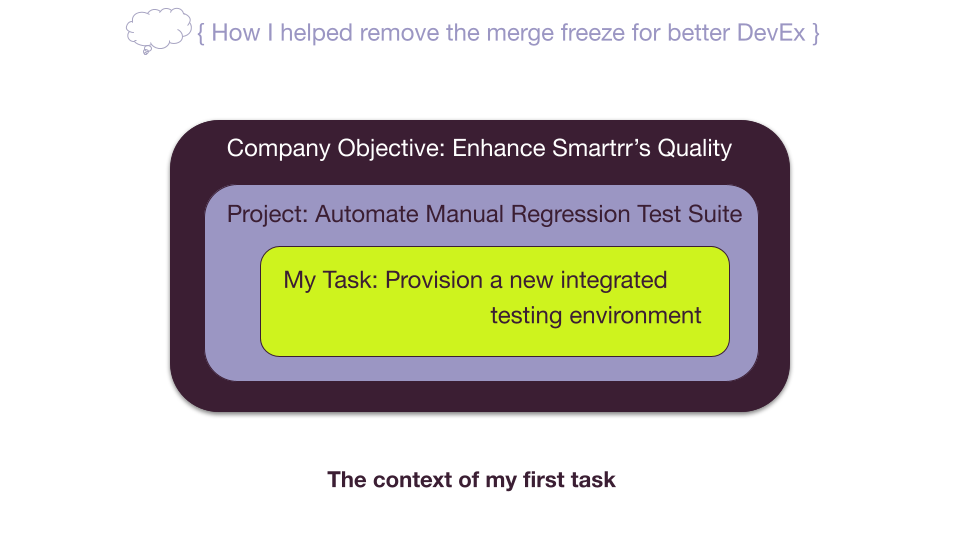

When I joined Smartrr, one of my first tasks was to help finish a project to provision a new integrated testing environment in Google Cloud.

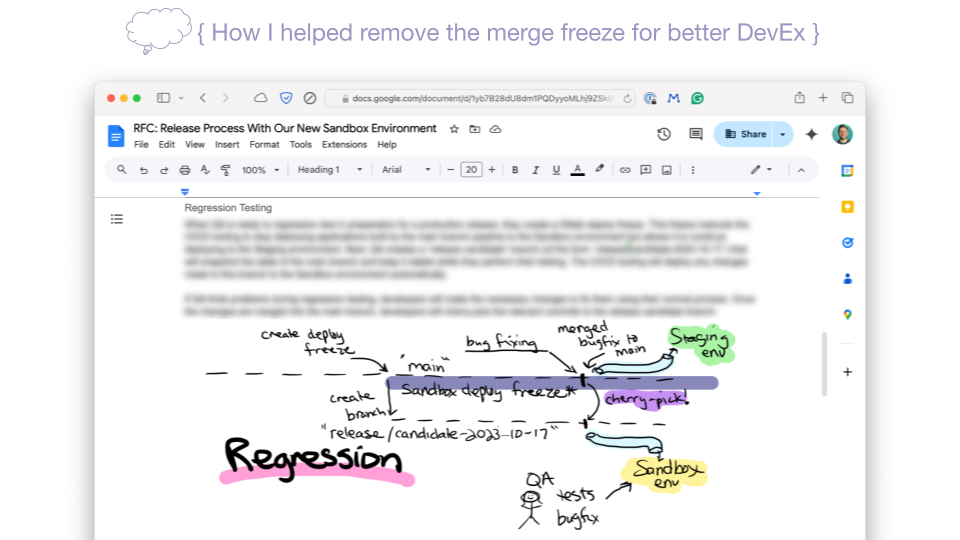

At that time, the process for performing releases was to stop merging patches into the main branch for 2-3 days while the QA team walked through their manual regression testing process using Qase, a popular QA test management tool. Any bugs found would be fixed immediately, and their patches would be merged into the main branch prior to a release being cut and deployed to production. During the merge freeze, the developers would continue building new patches for the main branch, but leave the merge requests open until the release was deployed. Then, developers would land their patches, and development would continue normally until it was time for a new release. The team was operating using a 2-week sprint, and the regression testing process would start roughly 3 days before the sprint ended.

While this process was working, it had its drawbacks. The fully manual regression testing process was slow, and often had unpredictable results because of a lack of unit tests in fundamental areas of the codebase. The development team understood the importance of quality, but was understandably frustrated by the merge freeze, which often resulted in difficult-to-resolve merge conflicts.

Context for my First Task

For context, the organization had recently renewed its focus on quality and stability when I joined, leading them to reevaluate every aspect of the Software Development Lifecycle. This resulted in a few new initiatives. Among these, they wanted to convert their manual regression testing suite into an automated suite that could be run more often and more efficiently. The QA engineers building this wanted a stable integrated test environment to run it against so that the application wouldn't change while the suite was running. So, this is where I come in, to help build this new environment.

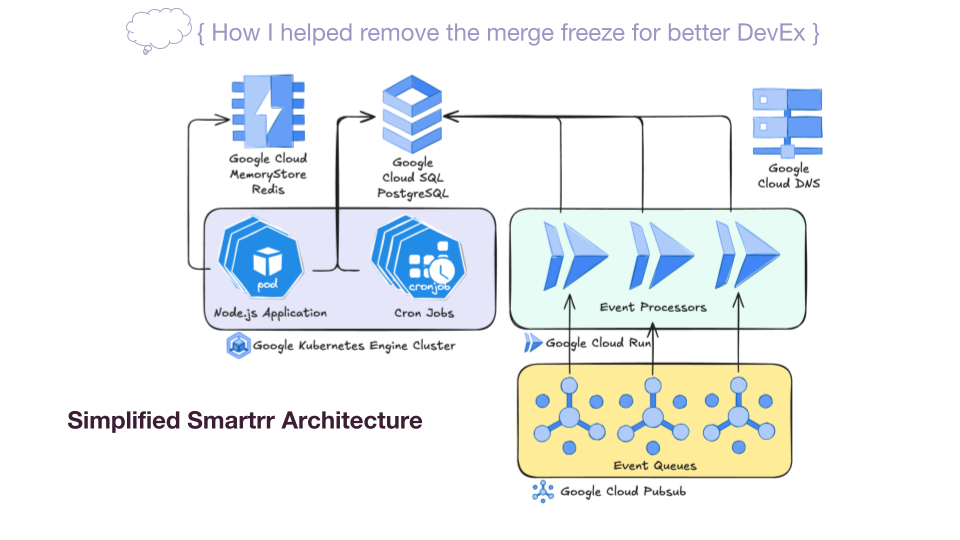

The application to be deployed to this environment was a monolithic Node.js web application, along with a collection of cron jobs, some Google Cloud Run instances, a PostgreSQL database, a Redis instance, some Google Cloud PubSub queues, and DNS. The application and its cron jobs were deployed to Google Kubernetes Engine. The source code was hosted in Gitlab. The GitLab CI config file was considered "arcane knowledge," and most were afraid to touch it for fear of breaking something.

Progress had already been made in building out the new environment. There was a new GCP project and a new cluster, and much was working - even Terraform was already being used to build out the infrastructure. I took this work and applied what I felt was best given the team, the circumstances, and the timeline.

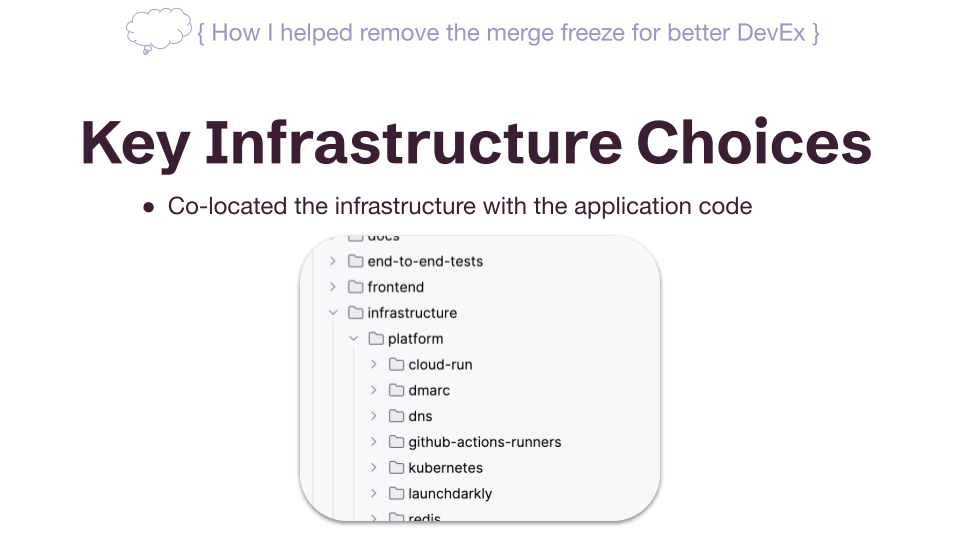

Pulling the Infra Code into our Monorepo

First, I felt it was important that the infrastructure code be colocated with the applications, so the developers would treat it as a first-class citizen. I moved the Terraform project into our monorepo and tied it into our automatic linting and dependency management tooling.

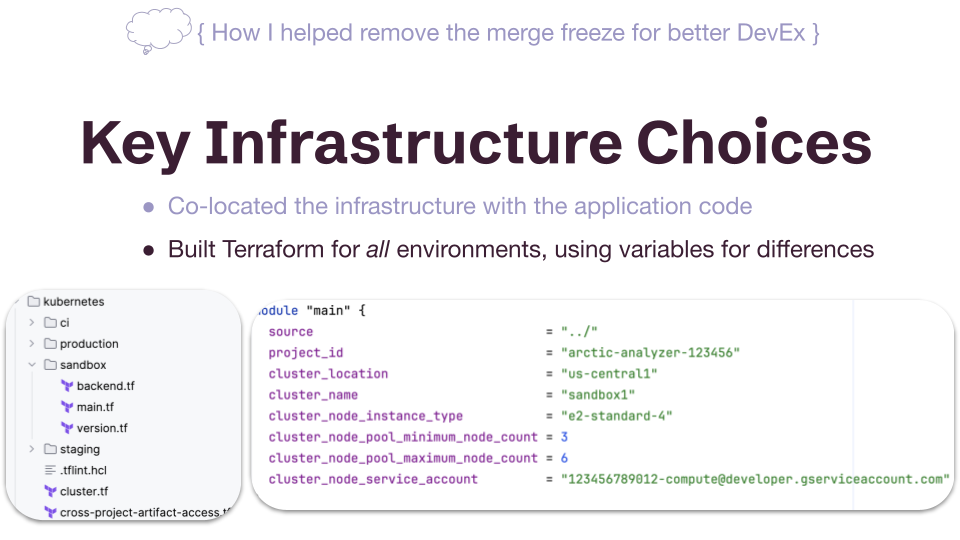

Terraforming All Environments

While choosing to build the new environment with Terraform was great, I felt it didn't go far enough because the other environments also needed this treatment. I went ahead and captured the existing staging and production environments in Terraform as well, then built the new environment's infrastructure by applying a different set of variables to those definitions. This ensured parity between the environments and helped us "heal" the places where they had diverged.

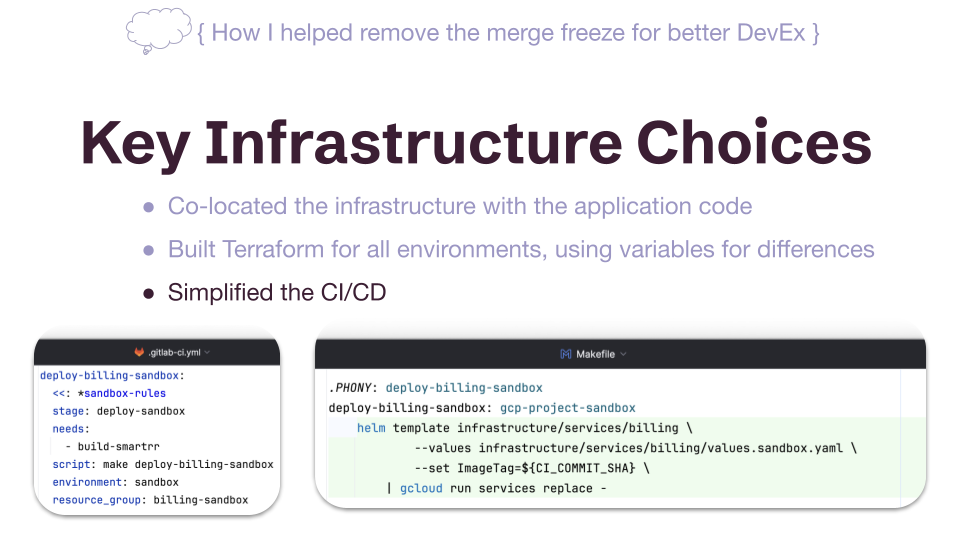

Simplifying our CI/CD

When Smartrr's CI was first setup, it used GitLab's Auto DevOps templates to get started quickly. Over time, heavy customization of this partially-obfuscated configuration made the CI process difficult to understand, so we decided to cut Auto DevOps out and explicitly define everything. We cloned the existing monorepo project to a new project in GitLab that had Auto DevOps disabled, then built out a new .gitlab-ci.yml file that retained the Gitlab specifics of the build, test, and deploy process, but split the majority of the commands off into a Makefile so they could be run manually. Once we had this working, we merged it back into the main monorepo and disabled Auto DevOps.

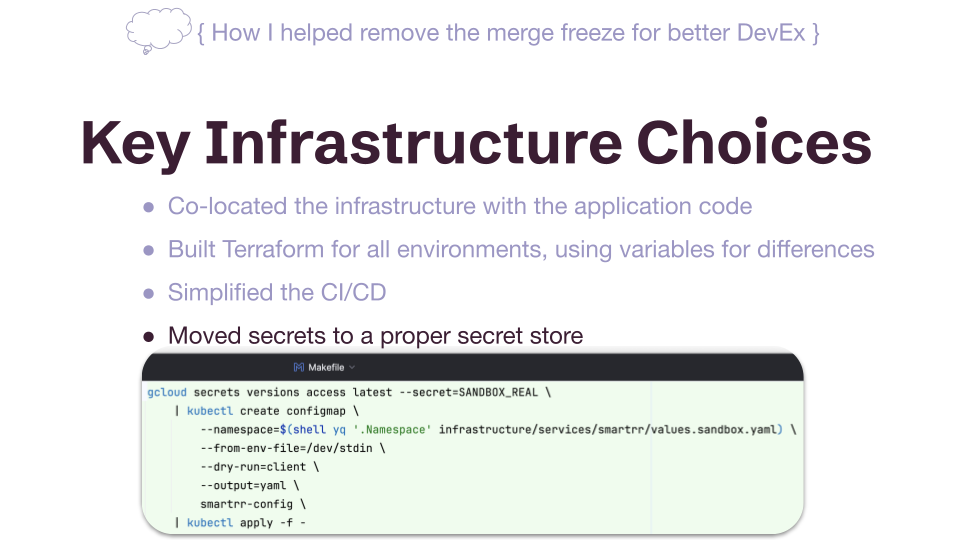

Using a Proper Secrets Store

Lastly, we decided to further decouple from Gitlab by moving our secrets. While rebuilding the deployment scripts, I moved all the application's secrets to Google Cloud Secrets Manager and automated the process of updating the Kubernetes ConfigMap from these values on each deployment.

Out of Scope

And there were, of course, some things we decided not to do.

Running the application in Kubernetes felt like overkill since we had a monolith. We decided to leave it this way, though, as it would have slowed our progress to migrate it elsewhere, and running it there wasn't actively causing any harm.

We also didn't set up any automated Terraform workflows since our infrastructure is relatively simple and does not change that often. We considered it a "nice to have" to automate it, but it's still a manual process, even today. I have it on my list to investigate Google Infrastructure Manager some time.

And while I did move our secrets into Google Cloud Secrets Manager, I decided not to setup a Kubernetes-native way to access these secrets. We weren't sure if we were going to continue to use Kubernetes moving forward, so I punted on this decision and setup a stop-gap. Time has shown that this decision was fine - and we've since learned we are sticking with Kubernetes, so I'll probably set up something like external-secrets operator the next time we go to deploy new workloads.

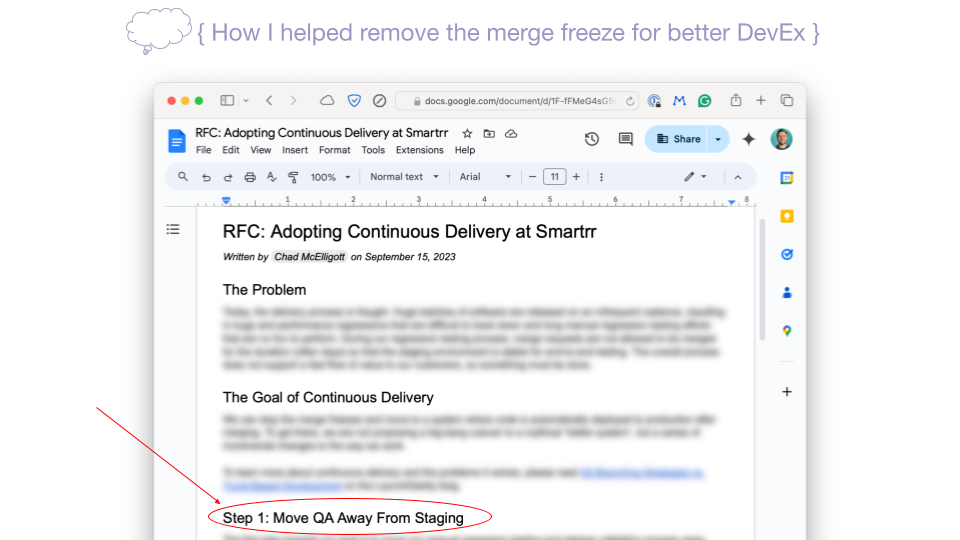

Sharing the Broader Vision

While we were still working on the new environment, I documented and shared our vision for eliminating manual regression testing entirely from our release process. Many were skeptical that we would ever achieve this, but folks were enthusiastic about moving QA to their own environment and removing the merge freeze, which was the first step to this larger plan anyway.

Mission Accomplished

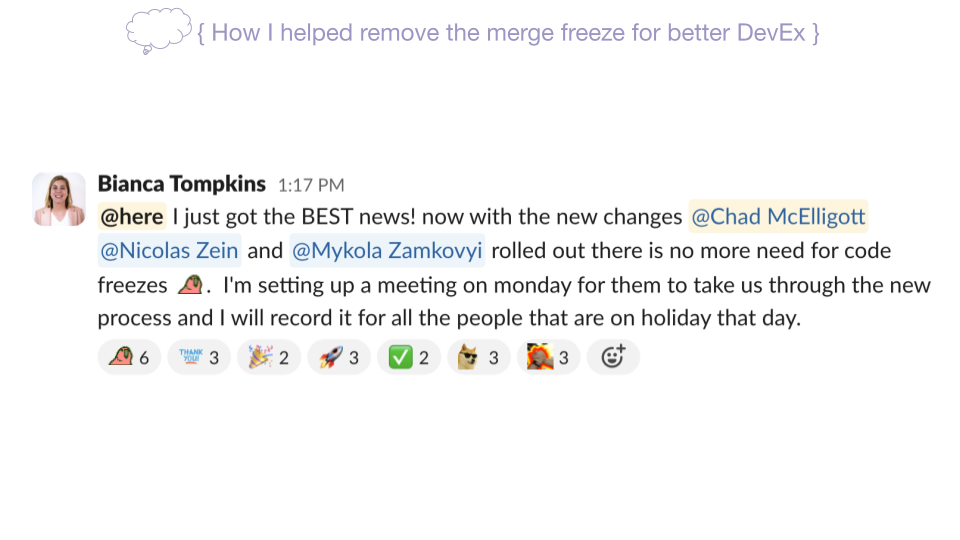

So after much iteration and a careful rollout of the infrastructure from staging, to sandbox, and finally to production, we called the project a success. The environment was released about a month after I joined and the QA team began using it in earnest.

And once the new environment was available, we updated our release process, so the QA team could block deployments from happening in their new environment while performing regression testing there. This new process freed up developers to merge their changes to main without restriction.

This is the release process we still use today. I do maintain that we will be able to achieve the vision of continuous delivery, it will just some iteration to get us there.

Principles Applied in Story 1

So, back to our 3 engineering concepts that we're exploring - DevOps, Platform Engineering, and Staff Engineering. How were these helpful in this story?

Well, Staff Engineers are eager to seek out anyone who can help, no matter what team or role they have at the company. While working on this project, I spoke with practically everyone in the company to clarify, verify, and lead with intent. I played a "tech lead" role on this project, driving the project to completion, managing scope, and making tough decisions along the way. Finally, I leveraged the project to make our infrastructure and CI/CD process more accessible and easier to understand, both of which are universal goals of a Staff Engineer.

While this was initially what you may think of as a "DevOps" project, I turned it into a platform project by altering the scope to fully manage our infrastructure with code instead of just the new environment. By making that change, Terraform is now the clear choice for all infrastructure moving forward. We're also less likely to encounter differences between environments as our infrastructure evolves, giving us a solid foundation to build upon. I did have to walk away from some nice-to-haves, but I felt these were good trade-offs given the lateness of the project and pressing priorities elsewhere.

DevOps principles were core to this project, of course. We leveraged infrastructure as code to manage our cloud infra consistently. We simplified and improved our release process once the necessary tooling was in place to support it. And I introduced the Request For Comment document format to the org to facilitate inclusive decision-making as we defined our new process.

So, that was my first project at Smartrr. It felt really good to hit the ground running and have a win so early on. QA got the environment they needed to run their automation without disruptive mid-suite changes to the application. Developers no longer needed to artificially delay merging their patches to the main branch. And the whole organization sped up a bit due to better tooling and processes for collaboration. I'd love to iterate on this process more some day, such as by building ephemeral preview environments or fully automating our regression testing. If these topics interest you, come find and we can chat!

Next, I want to shift gears a bit and show you another side of Modern Staff Engineering: getting involved in shaping the processes used to organize our work.

Story 2 of 2 - Iterating Towards a Productive Engineering Process

Over the course of my year with the company, I have pushed our leadership team to continuously iterate on the processes and practices the engineering group uses to organize itself to ship software. I believe there is no one-size-fits-all approach to building software, so I felt that by experimenting with different approaches I had seen work well in the past, we could eventually collect enough signals to lead us to practices that result in productive collaboration.

When I first joined Smartrr, the product development group all worked from a single board and would meet every day and walk through it, delivering status updates to the rest of the group. There was a lot happening! But when looking out over the Google Meet video call, it was clear that a lot of folks were checking out when it wasn't their turn to speak. As new features were being built, the responsibility of seeing them fully shipped felt diffuse - no single engineer felt this was their responsibility, so it often fell to the product manager. There was also no clear understanding of the technical architecture that was being constructed during feature development. In summary, there were processes in place, but I felt we could do a lot better.

Agile all the things

I've worked places that felt engaging, empowering, and thoughtful each day. I wanted to bring this feeling to my new group, and given my new role and the Startup environment and culture, I felt empowered to do so.

Smartrr does not have any formal engineering management in place, so I collaborate with my amazing colleagues, CTO James Turnbull and Director of Product Bianca Tompkins, to fill the gap and provide support to the team. Together, we regularly discuss ways to improve in all of these areas and more, then I draft proposals for any changes we want to try out. Each time we implement a new idea, we frame the change as an "experiment," which I've found reduces the friction of change and helps folks understand they are not a one-way street. We always make the goal of the change clear, so everyone can decide for themselves if we're hitting the mark or not. In this way, we make any sort of process change a group endeavor, and in our retrospective meetings, we discuss whether a given change is having its desired effect or not.

I'd like to share with you some of the process experiments we have run, the goals of these changes, and the outcomes we saw.

Experiment: Short-lived Feature Teams

First, we ran an experiment to move from individuals working tickets across the board to instead running short-lived feature teams. The goal of this is experiment was to build a sense of direct responsibility for the full lifecycle of feature development within engineering. We chose a lead for a feature, who in turn would pick a cross-functional team – backend, frontend, and QA – to work with them to implement the feature to it's outlined acceptance criteria. The outcome of this experiment was mixed. We definitely saw an improvement in team members' sense of ownership over a given feature, but not everyone wanted to be a lead or felt well suited to be one.

After trying this for a few months, we decided to move to a new fixed-team model with static leads that we call "squads". These squads run their own planning and retrospectives, giving them more autonomy and ownership over their process.

Experiment: Epic Kickoff Documents

Second is our epic kickoff document experiment. The goal of this experiment was to ensure that requirements are clear, and the entire team is on the same page regarding the scope of a project and the approach that will be taken prior to starting work. To make this change, we provided a template for teams to populate during a meeting together where they cover all agenda items highlighted in the document and any additional context they feel is important to share. This document can be referred back to throughout the project to clarify the original plan.

The outcome of this change was very positive! The document only served as a prompt, a way for people to not feel lost when first beginning these meetings and opening up communication between each another. The team members now feel these meetings are a good value for the time they spend, and they operate better earlier on in the project because of them.

Experiment: Group Code Review

Lastly, I'm excited to share my favorite experiment we've run – our group code review. The goal of this experiment was to reduce code review turnaround time, encourage discussion of code, and share skills between the engineers. To achieve this, we decided to try meeting twice a week in an optional 1 hour Slack huddle where developers can join to either review code or have their code reviewed by others on the call. A driver shares their screen and walks through a pull request, and the attendees share their thoughts and make suggestions.

This has had a huge positive impact on our engineering group. By reviewing each other's code in person, they naturally treat each other humanely and respectfully on the call and in comments outside the call. Comments made in the call result in thoughtful discussions about techniques and trade-offs, which leads developers to learn a lot from one another. Pull Requests never sit long because, in each session, we work to reach Inbox 0. More code reviews are happening now, even outside the group review sessions!

This has also given the team exposure to the benefits of pairing or grouping up for coding sessions, which I'm hoping to push more for as time goes on.

Principles Applied in Story 2

Let's check in with our modern engineering concepts again, and see how they have influenced this work.

Adjusting process for teams is usually thought of as the role of an Engineering Manager or Director, but in their absence, a Staff engineer with an interest in these sorts of improvements can get involved and help. Once the culture of continuous improvement has caught on within the teams, they will feel empowered by their agile processes instead of burdened and can take on the challenge of further process improvements themselves. Sometimes teams get stuck in process ruts that are dragging them down, but they're not aware or are used to it. Having a trusted Staff engineer shake things up and show a better way can be just the medicine the team needs to realize their full potential.

While much of the buzz around Platform Engineering tends to revolve around tools, my hot take is that process is a part of your platform. Process plays a large part in the speed and effectiveness of your engineering organization, so it should be thought of as an enabler alongside your tooling. An ineffective process is an impediment to a team's developer experience, so replacing it can be just as impactful as improving build times or reducing toil during deployment. Process is also a lot easier to change than tooling!

As for DevOps, well, consider the acronym CALMS, which is often cited when DevOps is defined: It stands for Collaboration, Automation, Lean, Measurement, and Sharing. The Lean part refers to using Lean processes to eliminate waste in the value stream. Iterating on your processes through agile and teaching others how to do so is a core aspect of DevOps!

I strongly encourage you to take a hard look at your processes and decide if you have room for improvement. It's a low-effort and high-impact change you can make that will benefit everyone.

Conclusion

I'm really enjoying my time working in a startup environment. At this stage of the company, I feel I'm able to bring my full self to the problems we are solving and can work across disciplines to help bring solutions to life. The ever-present time constraints force pragmatism, an important skill to cultivate no matter what industry or environment you're working in. The embryonic nature of the company gives me the opportunity to make a huge impact and set the company up for success by applying a modern approach to software engineering.

Staff Engineers often require both breadth and depth of experience to be successful in their role. Working at a Startup is a great opportunity for a Staff+ engineer to further develop their breadth of knowledge and perhaps try out an area that they may not have had a chance to dig into before. Have you primarily been working as a backend engineer, but you're interested in developing some React or BigQuery skills? A startup is a great place for this.

Platform Engineering will look different at different scales of companies. At a startup, you'll be able to sit down 1:1 with the developers to understand their pain points, then take on small projects to move the needle in a better direction. Building fast feedback loops into the development process is a great way to improve devex and help the developers help themselves in the future. And you'll want to ensure all your basic Software Development Lifecycle concerns are covered with industry-standard tools and techniques. Platform Engineering won't be a full-time job at a startup, but a technique you apply when the need arises. Remember, "A company's developer experience is a product, whether anyone designed it or not." So take a bit of time to design it.

I hope you agree with me that DevOps is very relevant at a startup. Putting in place the culture, processes, and tools that accelerate value delivery to customers and make a company a humane place to work is very rewarding for everyone involved. So if you're a DevOps enthusiast and are considering working at a startup for the first time, I think you'll find you have a lot to bring to the table.

Thank you 🙏.

Many thanks to Chris Hodges, Kyle Kurz, James Turnbull, David Lee, Patrick Steadman, and Samuel Galarneau for reviewing and providing feedback on the early drafts of this talk.